Philips (who are not sponsoring me to write this!) sell a line of light bulbs here in Denmark which they advertise as “Warm Glow”:

I think I’ve also seen these marketed in the past as “Dim2Warm” or “Dim to Warm” but I can’t find any reference to that name any more. Maybe I was imagining it?

These bulbs are quite neat, and one of the best recreations of incandescent bulbs in my opinion. Not only do they have a frosted glass ampoule, >90CRI and no flicker (at least that I can see – and I’m quite sensitive), but their unique feature is that as you dim them, they reduce their colour temperature, becoming warmer and more reddish. (Note the potential confusion: a “warmer” colour refers to a lower colour temperature!)

This creates a really compelling effect and avoids the issue whereby an LED light can look, for lack of a better term, sickly or artificial as it’s dimmed.

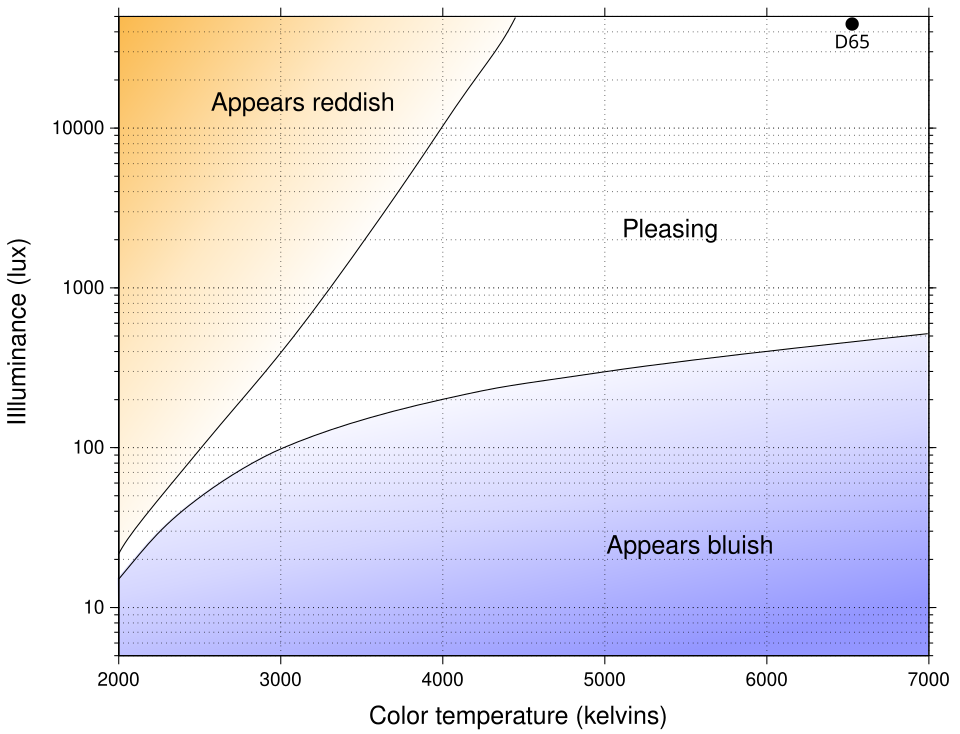

This happens because our eyes are used to seeing black-body radiators, which become warmer in colour as they cool and become dimmer. When we see something dim without its colour temperature changing, something feels off. This is said to extend to our perception of illumination as “reddish” or “bluish” more generally:

The Kruithof curve purports to define the range of colour temperatures and illuminances which are perceived as “correct”, rather than seeming bluish or reddish, which again shows that we expect colour temperature to decrease as brightness decreases. It’s interesting how this suggests that at very low levels of illumination, even a very warm white such as 2000K would be perceived as “bluish” and at higher levels of illumination, even 4000K would appear reddish, although most people would feel like this is a very cold and clinical lighting if it was used indoors.

Back to LEDs

Since incandescent light bulbs produce light through black-body radiation, they naturally produce this warming effect when dimming. In an LED bulb, this effect needs to be produced artificially, presumably by adjusting the ratio of the output of two or more different emitters.

I wanted to reproduce this effect in my own lighting projects, which got me wondering: how exactly should I vary colour temperature with brightness? I figured I should emulate the colour temperature vs luminance curve of a black body radiator, but I couldn’t find any reference to this curve, so I set about making it myself.

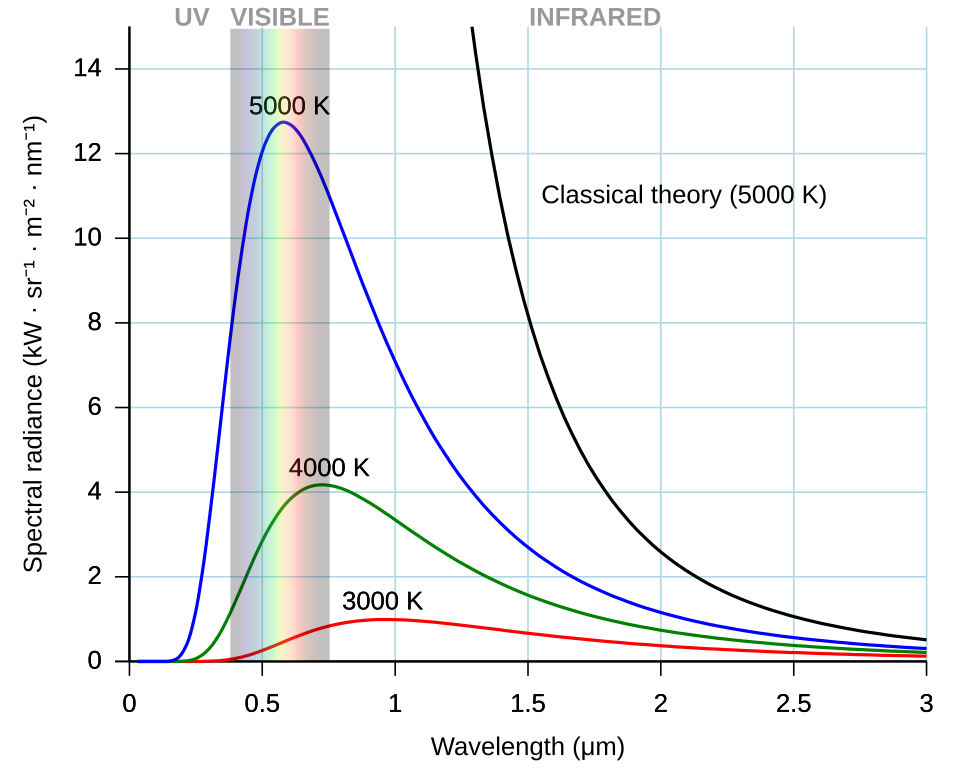

My method was to model the black body radiation using Planck’s law:

This gives the radiated energy (per steradian-metre-squared-hertz) as a function of wavelength and temperature, looking something like this:

Luminous Efficiency

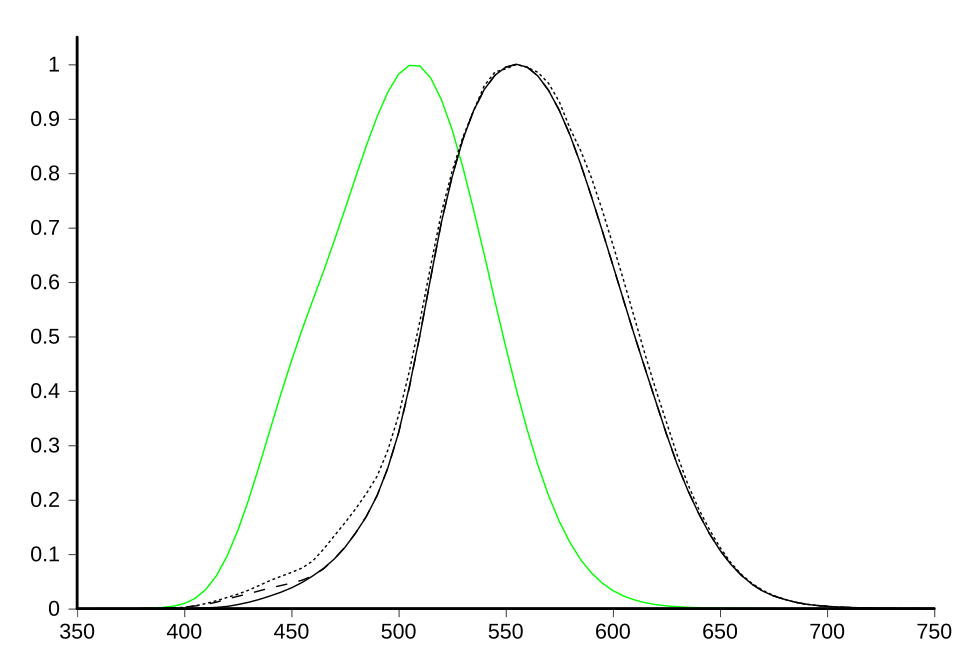

The next step is to translate this into the perceived brightness of that spectrum, for each temperature. This requires that we apply a model of the “weighting” of wavelengths in human vision. For a given amount of illumination, we tend to see green as being much brighter than blue or red. And of course, anything outside of the visual spectrum isn’t perceived at all. A model for this variation is called a luminous efficiency function.

In trying to find such a function, I stumbled upon the Colour & Vision Research Laboratory. It looks like a great resource for data on colour and human perception of it. I used the Stockman and Sharpe 2 degree luminous efficiency function, which you can see as the dotted line here:

The other black lines are other models for the same thing, while the green line is for scotopic (night) vision, so isn’t really relevant here.

Putting it Together

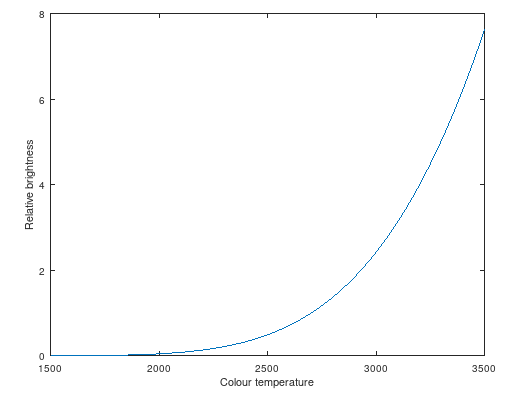

Anyway, by multiplying the spectrum with the efficiency function and integrating over the visible light band, I got relative brightnesses for a given black body radiator as a function of temperature:

The actual numbers are arbitrary, so here I’ve normalised for 2700K -> 1

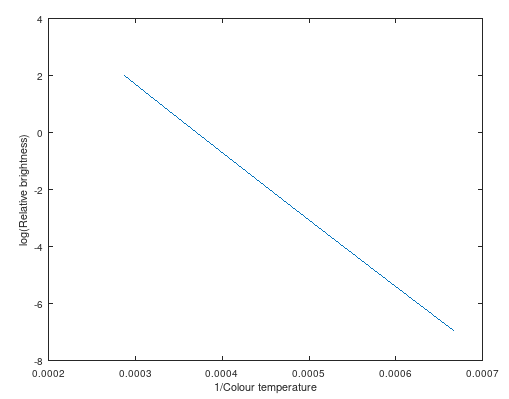

It turns out that if you plot log(brightness) against 1/T, the relationship looks more or less linear:

The slope of this graph is -2.36 * 10⁴

I repeated this using the alternative and more dated CIE 1924 luminous efficiency function and got similar results, with exactly the same slope (to the 3 significant figures given).

Conclusion

For a given black body radiator, brightness (B) and colour temperature (T) are related by:

Where k is a constant to account for the size and geometry of the body and the observation point/area.

This means that, for example, a lamp which produces 1200 lumens at 2700K will produce 165 lumens at 2200K:

I plan to share a project here soon making use of this relationship but I thought that for now, this was a useful enough result to share by itself!